Reflections on Agentic Coding

January 17, 2026

2025 went out with a bang in the world of software engineering. Coding agents like Claude and Codex and Copilot and the recently viral OpenCode have transformed the way engineers work on a daily basis. Prior to 2024, AI was more of a joke than a tool people took seriously. I myself remember working as an engineer in 2024 and barely using ChatGPT to solve some problems in languages and tools I wasn’t as familiar with, asking it what problem space I was in and seeing if it could solve tricker problems for me. I primarily used VS Code to write all my code, and it was still me actually writing it. No tab complete. No AI agents. Just good ol fashioned ass-in-seat, hands-on-keyboard coding.

Towards the beginning of 2025 however, I started to adopt Github Copilot into my coding tasks. It pretty much all started out as just using tab-complete to write code and tests. I wasn’t really delegating or handing off tasks to it, more so allowing the tab-complete to save me some time and effort, while watching it be kind of correct some of the time, making manual adjustments, and coming up with something that worked well.

Throughout 2025, I slowly started adopting agentic coding. First, I started out using Windsurf’s SWE-1 model within Cascade to generate code changes and files that I needed. It worked ok, but I found that a lot of the time I needed to go in and do some pretty significant rework of a lot of the stuff it generated in order for it to be ready. Granted, I was a lot worse at prompting around this time too, so it was probably just as much a reflection of my own skill using agents as it was the agent itself.

Even with the rework, I was still finding in-editor coding agents to provide a decent productivity boost: I couldn’t fully trust the work, but I was finding the models capable of getting me around 70% of the way there, and it was still a lot faster than me writing it out by hand, telling VS Code to make me new files when I needed it to, copy-pasting test files and tab-completing them until they passed… AI was becoming more of a companion than ever.

Throughout the summer and going into fall, as Claude Code gained more popularity, I started trying to figure out if it was possible for me to use open-source and free models locally as an alternative to paying any AI subscriptions. As it turns out, running LLMs locally is really challenging and resource-intensive. I started to realize that as nice as my M1 Pro with it’s 16 GB of RAM really is, it was nowhere near enough hardware to run any good LLM locally.

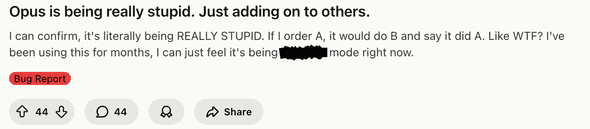

October was really where I caved: I needed to understand what all the agentic coding hype was all about, and that’s when I did some research using ChatGPT and Claude to figure out which offering was better: Claude Code or Codex. In retrospect, I made the right decision to use Codex as opposed to Claude. Reddit in recent months has been blowing up with posts about how bad Claude has been working for them:

Meanwhile, I’ve been using Codex 5.X models for a few months, and I have really enjoyed using them. I haven’t really many, if any, issues with how the models work. In projects using technologies like NPM that I’m very familiar with, it’s been a great companion. In projects that use technologies I’m not nearly as familiar with, like iOS development, agents have been able to help me go from having 0 code written up, to having something workable and iterable within a matter of hours. The skills that I lack are what these coding agents are able to help me make up for in my overall skillset as an engineer.

What I do notice, however, is how much these models really end up being more of an extension of me as opposed to being an omipotent being of infinite knowledge. One fairly discreet example is how models approach creating great UI/UX. I will be the first person to admit that I am nowhere near the best at creating intuitive and friendly user experiences. I do know how to work off of mock-ups and discreet designs, and I can be an amazing partner to any UX designer. However, it would take me more time to create great user experiences without the help of a designer or a design system to work off of, agent or not.

I’m sure if I was better at crafting wonderful user experiences, I could tell an agent what I wanted and how to accomplish it. Heck, even if I was able to create a good mock-up or two myself, I could ask Codex to work off of a screenshot of a prototype. I didn’t even know until very recently that Codex was even capable of this!

Along the way, there are some tips and tricks that I’ve learned that either you’re going to read and say to yourself “wElL dUh, tHis iS ObvIoUs” or “huh, I haven’t considered that before, maybe I will now”. Hopefully these will be useful to you:

Context Matters

Providing your tools with as much context as possible is going to always yield better results in the long run, whether you’re working with existing or new code. I have yet to fully adopt planning mode in a lot of agents because… Well, frankly I find it more useful to just give it a list of instructions and functionality that I want. I think if I actually wanted help with actually planning out a new project, I’d likely try it, but more often than not I usually have a pretty good idea of what I want the agent to work on. I’ll typically list everything out that I want and allow the agent to iterate on it.

For example, if I was going to create the internet’s favorite CRUD starting project,

a TODO app, I’d likely start building the app by using my framework of choice’s Getting

Started guide to create a scaffold. I’ll explain in the next section why I might do

this. So I might start out using npx create-next-app, just as an example, if I wanted

to use Next.js. Depending on what else I think I might need, like Auth, a DB, and styling,

I might also go and do some research to see what else I could take advantage of to speed

up development. Tailwind and Supabase are two pretty popular options, so I might craft up

a prompt telling the agent what I want the app to do, and what I want it to use to

accomplish my goals:

> I would like to create a small project that will display a web page that shows a list of TODOs:

* The app's landing page should prompt the user to login if they haven't already. There should also

be a button prompting them to sign up if they do not have a login.

* Once logged in, the user should see their list of things to do. If they don't have anything,

write a motivational message encouraging them to start adding things.

* Allow the user to add something to do, and for each list item, allow them to click it to navigate

to a page where they can update the item with more details.

* Allow them to put a due date, a more detailed description, a priority, and an emoji that will display

on the TODO list next to the item.

* On the TODO list page, allow the user to mark items complete. When they mark an item complete, display a

confetti animation. Keep completed items at the bottom of the list.

* After 30 days, archive completed and deleted items from the list and keep them in a separate

section of archives where they can see them, but not interact with them.

* Allow the user to sort the list by due date, priority, and alphabetically.

I want you to use Tailwind for styling, react-icons for any icons you might need, assume that this app will be deployed on

Vercel using Next.js, and use Supabase for Auth and DB.This all assumes that you have a good idea of what you want your architecture to look like, and you know what services you want to take advantage of. If you don’t, the other thing you could do is use a combination of ChatGPT chat and deep research modes to perform an analysis of what services might be a good fit based on what your requirements are. Both ChatGPT and Claude offer research modes in their chat clients if you have a subscription that allows you to use their coding agents too.

Keeping Existing Tooling in Context

One thing I continue to find is that in some instances, coding agents don’t quite understand that some source-controlled code is auto-generated by means other than agentically, or that there are standard tools that frameworks provide to generate necessary code, files, and configuration. This could either be in the form of those tools existing at the beginning stage of a project, or during the development of a project.

In instances such as this, I tend to lean on using existing tooling first to generate a scaffold, then turn to the agent to help with finite business logic.

As an example, I’ve been using OpenAPI for years to help generate API specifications for my RESTful services, as well as to generate clients. I’ve found that in some instances, rather than using OpenAPI command-line APIs to generate a client, it tends to want to modify the client as if it’s a hand-written file, as opposed to using other commands to generate clients based on a spec.

Another example: whenever I’m starting a new project, I notice that if I use the agent to actually create the project scaffold, sometimes it ends up creating something that is out of date, or it tries to create a project that under normal circumstances is incomplete.

In cases such as these, I may interrupt an agent in order to use existing tooling, then turn it loose to help with the rest. Either that, or I’ll give it more explicit instructions:

> This repository contains a client package that is generated using OpenAPI. I've

pulled down the latest spec. Use `npm run generate:client` to generate the client

package, then use `npm run build` to ensure that all the rest of the code still

compiles.Adding this kind of tooling to your repo’s instruction files (like AGENTS.md or a

similar file) can help with ensuring your agents have context to what kinds of tools

it should use for certain tasks. Balance this with the time it takes you to just run

these tools yourself of course, but if you’re running a lot of these commands, it may

behoove you to teach the agent to use them instead.

One-Shotting Using Mentions

Agents fairly often might just try to generate code using practices that the underlying model has been trained on. For many teams, this isn’t always the desired behavior. Sometimes a long-established pattern or practice is what is desired over whatever the model thinks is best.

Let’s say you’re working on a RESTful service, and you want to use an agent to help you add some new functionality to it. There are already some well-established patterns for breaking down how the code is structured from the routing, down to how the data model is built. You might have a prompt like this:

> I need a new set of endpoints built out to help manage TODOs in this service:

* Create CRUD endpoints for all the TODOs.

* Create a data model for the TODOs that relates many TODOs to one user.Every online course that teaches you how to use Generative AI teaches the concept of zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot prompting. The above prompt is an example of a zero-shot prompt: you’re telling the model what you want, and you’re going to let it decide how it does it. You’re not providing any examples of existing code.

Will this produce code that works? Possibly. Will the code follow best practices that are present in the repo? Probably not. The model is very likely to yolo in what you’re asking for without giving a second thought to everything else around it. It very well might miss important considerations like security, telemetry, and performance optimizations already present in other parts of the code.

You can help aid the model by providing it with more context in the form of a one-shot or few-shot prompt using file mentions. File mentions allow you to refer to existing code in your instructions. By adding mentions to a prompt, you’re turning your existing zero-shot prompt into a one- or few-shot prompt, contextually providing examples that the model can leverage to generate better results. The above prompt might change to:

> I need a new set of endpoints built out to help manage TODOs in this service:

* Create CRUD endpoints for all the TODOs. See @src/api/controllers/foobars.controller.ts

for an example of how to create a controller for TODOs. Ensure you add all the same

logging and security annotations to the controller methods that are present in the

foobar controller to the new one.

* Create a data model for the TODOs that relates many TODOs to one user. We use Prisma

for our ORM, so I'd recommend adding the new schema to @src/prisma/schema.prisma

and running `npx prisma generate` to generate the new model. Ensure that the model has

row-level security built-into it, like we did with the foobar migration: @src/prisma/migrations/20250116000000_add_all_teh_foobars/migration.sqlZero-shot prompts, I have found, are really not as useful if I’m working with an existing codebase with well-established patterns and practices. If you want the model to be more creative in how it solves a particular problem, zero-shotting may be a better route to take, otherwise it might try too hard to use the context provided from a few-shot prompt.

Dependency Upgrades

Technical debt still runs rampant in many organizations. Outdated dependencies are not only ticking time bomb for security vulnerabilities, but as dependencies evolve, they become beneficial for your end-users in the form of added stability, performance, and features.

You know what really sucks about outdated dependencies though? Especially in Node projects? Updating all of them. I thought updating dependencies in Java was a pain whenever I was knee-deep in Maven dependency hell. I still to this day hate hate hate updating any frontend Node project dependencies, because pretty much everything is bound to break when you do. Agents, though, are able to iterate on upgrades, linting, building, and test runs until everything just works™️.

In many projects, I’ve asked agents to help upgrade dependencies while ensuring that all of my quality checks still pass. For example, earlier today I asked Codex to upgrade all the dependencies for my blog:

If you were to run `npm outdated` you'll notice that several dependencies in this project are outdated. Please upgrade the

dependencies in here to the latest for each, ensuring that everything will compile still by the end using `npm run build`.Recently, the company I work for also went through a rebranding, which meant that our design system also went through a pretty drastic change. I had gone through and updated one of our core component libraries to match this new design system and include updated branding. As part of this, I had also written documents regarding upgrading from older versions of this library to the new one in the form of markdown.

Normally, taking an app from an older version of this library to the new one would have required a lot of manual rework of existing components that consumed that library. However, I was able to migrate an older app to using a new version of this library using Claude through Github Copilot CLI by copy-pasting much of the migration documentation I had written into the prompt I had made to tell it to upgrade the other dependencies in the project.

Claude, with a little bit of handholding, was able to upgrade the dependencies, as well as use the context from the documentation I wrote to successfully migrate the app to utilize the new branding and design within our core component library. I got a bit scared when it started to think that it would be a good idea to temporarily disable the script we had that used eslint to lint our code… But after a few more explicit prompts and guidance, it was able to get the linting working again.

For shared components and libraries, this recent experience made me realize just how important documentation is to a project: if I hadn’t written any of those documents explaining how to upgrade from an older version to the newer version, this process would have been a lot more painful: Claude would have had to make more assumptions about the code and the libraries than it had to previously, and likely would have ended up making more mistakes than it would have without the documentation.

Tooling Preferences

Speaking of the good ol days of coding by hand: I remember while working at Cerner, every dev and their mother had their preferences of IDEs/editors they swore by. All the Rails folks used Sublime. Java devs were all split between IntelliJ and Eclipse. .NET Devs didn’t even touch their code unless they had a license to Visual Studio Enterprise. When teams started integrating Node into their codebases, everyone started out using editors like Sublime or Atom until Microsoft released VS Code.

I think what we’re seeing in the industry now with agents is akin to the days of arguing which editors were supreme! There are people who swear by Claude Code, others who only use Codex, and there are growing numbers of people who prefer to have access to several models and agents through subscriptions to Github Copilot, Cursor, Windsurf, or Antigravity.

In deciding which agent I wanted to start using, I actually had Claude and ChatGPT perform web research and sentiment analysis on which subscription might be better. Considering all the responses that Claude and ChatGPT gave me, I ended up subscribing to ChatGPT. Through continued use and experimentation, I’ve found that Codex not only works well for what I want it to do, but I also find it behaving more efficiently than other models have. The behaviors of how it executes really matters in terms of being able to autonomously work towards “completeness”, and I’ve noticed that while the quality of work that each model produces is pretty comparable, how each agent behaves can vary greatly:

Typically if I have a list of instructions or requirements that I want the agent to follow, Claude and Codex tend to take very different approaches to completing things. Pretty much every model will take my instructions and compile it down into a plan of tasks that it wants to perform. It basically goes through it’s own little planning mode before executing. No biggie.

What is an issue though is the continuity of execution: despite the model creating it’s own plan of tasks, Claude tends to do one or more subsets of the plan and then it just… Stops? It’ll complete some things and then just say at the end something like:

Ok, so here's all the stuff I did:

// insert list of accomplishments

Whenever you're ready, let's move onto the other tasks that you've asked me to do!But… But… But I do want you to do the rest of that stuff! I’m not ready later,

I’m ready right now! What do you think you’re doing? What’re you stopping for? The

biggest value-add of an agent is to delegate things that it can automatically do for

you so that you can spend more time on other things that it cannot. What’s with

stopping partway through and waiting for me to type continue and hit Enter?

I will say though: this is an issue that I’ve yet to run into with Codex. Codex as a coding agent is pretty good at coming up with a plan and executing it continuously. In contrast to my experience with Claude, I once asked Codex to generate some files for me that hepled generate levels for a game I was working on. It created a script to generate the levels instead, but what it did after that was pretty interesting: it actually ran the script, which took several hours to execute, and verified the results. I don’t believe I ever had to tell it to continue before.

I will reiterate though that so much of my desire to continue using Codex over Claude is preference. I don’t think that Claude is inherently bad as far as coding agent models go. In fact, from my usage of both, Claude can hold it’s own against Codex in terms of quality and internal design. The best advice I can really offer regarding preference is to just try out new models and agents and tools as they become available, and see which ones work best for your workflow, use-cases, and team.

With how rapidly these models are evolving, the tools are changing and getting better and easier to use, and how the industry continues to adopt them in new and innovating ways, engineers will first and foremost keep their fingers on the pulses of the industry to understand how these tools are changing and evolving and what is becoming available. Secondly, they’ll need to have more fluid preferences than they previously have had.

I’ve used VS Code-based editors for nearly a decade. In contrast, I’ve used several different coding models and agents. The code didn’t change. The frameworks and libraries didn’t change.

The tools changed. I’ve changed along with them.

The tools will continue to change. I’ll continue to change along with them.

Buying Time Back

Beyond the terminal, outside the editor window, and beyond your hard drive, there are still other things as a software engineer that you’re responsible for. Design, documentation, backlog grooming, code reviews, yourself, etc. The time you save automating your coding work can be used to propel you in so many other ways.

When was the last time you had an “and” project that you really thought would add a lot of value to your organization? When was the last time you felt like you had any time to actually dedicate to it? I know for a fact many of you out there probably have something you want to learn more about. Take the time you aren’t coding to do the more manual parts of your work, to learn or experiment with something new, to collaborate with or provide mentorship for your colleagues, or read one of those books you bought but never finished because you had too many features with approaching deadlines you needed to ship.

I talked about this in a previous post, but one thing you’ll need to make sure you do is spend more of your time reviewing code. Not just other people’s code, but also the code that you’re delegating to agents. I still fall into this trap and I have to keep reminding myself that as good as some of these agents are getting, they still make mistakes that could be resolved simply by reviewing the code and making a few edits before sending it to the rest of your team.

If you are working on something that might require changes across multiple codebases, using agents is a great opportunity to delegate the changes to multiple agents to coordinate changes across multiple repositories. If you have multiple tasks you’re assigned across multiple repos, this is an even greater opportunity for delegation!

The only thing I haven’t done yet is delegeting multiple sets of changes to the same

repository without having multiple copies checked out at once. If I figure out how to

do this while trusting an agent with git access, I’ll share later 😅.

That’s a Wrap!

Well that was a lot of thoughts I spewed for a Saturday. I hope you found some of this helpful, interesting, thought-provoking, or garnered some other kind of positive reaction from you. Wherever you are in your AI-fueled journey, I hope this post has motivated you to continue to learn and develop your skills!

If you have follow-up comments or questions and you made it this far into the post without bouncing, you can always reach out to me on any of the social medias at the bottom of the page!